- Home

- Laura Ling

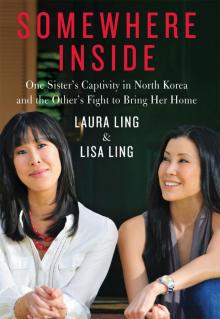

Somewhere Inside Page 8

Somewhere Inside Read online

Page 8

One day when Lien was on a trip to downtown Sacramento to purchase bean sprouts for the restaurant, she met a factory worker named Mrs. Wang who had just recently come to the United States with her two daughters, who were twenty-two and twenty. The three women were literally fresh off the boat; they didn’t speak any English, only Taiwanese and Mandarin. So another factory worker served as interpreter for Mrs. Wang and Lien, who spoke only Cantonese and English. The worker told Lien that Mrs. Wang’s younger daughter was quite beautiful and that her mother was pressuring her to marry. At the time, Doug, who was thirty-one years old, was dating a Caucasian woman, which bitterly displeased Lien. She suggested that Mrs. Wang’s daughter Mary meet her son, Doug.

This was our mother, Mary. She was the middle of seven children and the loneliest. Her father was uneducated, but for a time he had been one of the richest and most powerful men in Tainan City, Taiwan. His name was Wang, but he was known as Black Dragon and he was one of the leaders of Tainan City’s underground. He owned hotels, some of which were fronts for brothels and casinos. These side businesses paid him handsome returns. During the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, his businesses serviced Japanese soldiers, even though he hated them. His authority was such that local politicians running for office had to seek his approval if they had any hope of claiming victory.

When he was twenty-four years old, Wang noticed a shy but beautiful country girl at the spring festival. He couldn’t take his eyes off her and sent for someone to recruit her. Rather than putting her to work, he made her his first wife when she was nineteen years old. They eventually had seven children together over the course of twenty years. But only two of their offspring really mattered—the boys. During his marriage to Mrs. Wang, Wang took on two concubines with whom he fathered twelve children. Wang claimed a total of nineteen offspring, but it was rumored that many more children bore his genes. Mary’s only contact with her father was when he came to their house, patted the girls on their heads, and gave them a few dollars. He spent most of his time with his other wives and the other women he paid. Mary’s mother grew to hate her husband and warned little Mary to be cautious of men. Mrs. Wang never knew what love felt like, and her fourth daughter would never know it either. Her mother’s words always stayed with her—never trust men.

Mrs. Wang ran one of Black Dragon’s legitimate hotels. Wang’s second wife ran the ones in which brothels operated. From time to time, Mrs. Wang would have to drop things off at the second wife’s hotel. The things she saw there disgusted her, and she grew increasingly resentful as the years went by. She tried to shield her girls from the scenes of debauchery that surrounded them, but it was no use. On a few occasions Mary was sent to take things to the different businesses. Listless and tired workingwomen frequented some of the hotels. Young Mary once saw a woman with red lips crying in a room. She wanted to help the woman, but she was only a little girl and her mother told her to stay away from “them.”

Later that day, police officers and an ambulance arrived. The woman that Mary saw crying had hanged herself. The ambulance workers carried out the body, which was covered in a sheet. The only things visible were the woman’s high-heeled shoes. Mary never forgot what she saw. It made her heart hurt. Mrs. Wang began to stash away large sums of money in places where no one else could find it. She knew that one day she would find a way to take her children, leave, and never come back.

The year Mary finished high school, her father lost his entire fortune to gambling and could no longer support his families. Mrs. Wang saw this as an opportunity to leave. Her eldest daughter, Jeanie, had gone to the United States and married an American citizen. Mrs. Wang temporarily left her three youngest children with an aunt and took Mary and her sister Ruth to live with Jeanie and her husband in Sacramento.

Mary and Doug’s first meeting was pretty awkward, considering that they knew their parents had as much as married them off. But he did find her attractive, albeit too skinny. They could not have been more different. Doug was content with a simple existence of fishing with the boys and eating his meals in front of the TV. Mary was ambitious. She loved nice clothes and wanted to see the world. On top of it all, they could barely communicate. Mary had difficulty with English, so for the most part they just smiled and exchanged polite gestures.

Doug was on his best behavior, but that didn’t last long. He was ten years older, and he’d already had a lot of experience going to bars. On their first dates, he brought Mary along, but she hated the scene and didn’t like Doug’s friends. She thought they were crass and rude. She didn’t drink; he drank a lot. They started going to movies where they didn’t have to talk much. Four months later, on March 8, 1969, they were married.

Their first year of marriage was decent enough. Doug had been working as a supervisor at McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento, and Mary went to school to learn English while working on the weekends as a waitress at a local Chinese restaurant.

They hardly saw each other. Their inability to fully understand each other prevented them from developing a real intimacy. Even so, he came to love her. She, on the other hand, could never forget her mother’s words to her, “Never trust men.” She couldn’t love.

Life was just perfunctory: they worked all day, and at night when they were home, they watched TV. This went on for years, and eventually Doug started going out more with the guys, hitting up the bars a couple of nights a week. He came home smelling of beer, talking loudly, and rambling on about how much he loved his wife. Then he would stumble around until he eventually passed out in bed. This made Mary feel lonelier than ever, so she decided it was time to bring a new friend into the world. On August 30, 1973, I was born.

I was only two years old when my mother’s belly started growing bigger and bigger. I recall Mom telling me that my baby brother or sister was inside of her, and the thought of it sent such a shock through me that I still remember it to this day. It was amazing. I kissed my mom’s tummy and talked to it all the time. I knew it was a girl; it just had to be a girl—that’s how much I wanted a sister. On December 1, 1976, Laura came into my life.

From the day she arrived, I remember feeling like we were a team. I was glad I wouldn’t have to deal with the family drama by myself, even if Laura was a baby for much of it. Just knowing I had a partner made things a bit easier to bear, especially because our parents fought throughout our childhood.

Mom wanted to do things like go to the movies and try new and different restaurants. Dad hated movies and would only eat in the same Chinese restaurants. Plus, Dad worked all the time, and on the nights when he’d come home early, he’d crack open a beer or two and sit in front of the TV for the rest of the night. Mom seemed detached and depressed a lot. But none of this meant they were bad parents. Despite the tumult in their relationship, both of our parents were nothing but loving to us all of our lives. Some of my fondest memories include the nights when, with her melodious voice, Mom would sing us to sleep. She always sang the same song, “Edelweiss,” from the musical The Sound of Music. Of course, because of her difficulty with English, it always came out “A dell voice.” To this day, Laura and I still sing it that way.

On the nights that he worked late, Dad would return home and tiptoe into our room thinking we were asleep. He would lean down and give both of us little pecks on the forehead and whisper, “Daddy loves you.” I loved the way his prickly mustache felt on my skin; I loved how much he loved us.

I was seven years old and Laura was four when our mother and father finally decided to go their separate ways. We stayed in Sacramento with our father because our parents didn’t want to uproot us from our school and community. Plus, we had Grandma. Dad’s mother, Lien, lived with us until she was struck by senility when we were teenagers; she was our source of stability. Grandma was a self-assertive woman, particularly when it came to her faith. She always felt the need to “save” people, which sometimes embarrassed us. It was hard enough to be among the only Asian kids in our community, but Grandma would

make the neighborhood kids sit through obligatory Bible study whenever they’d come over. She would make us memorize verses and quiz us from time to time on what they meant. Needless to say, our house wasn’t the most popular destination for kids.

Grandma thought Halloween was a pagan holiday, so every year on October 31, she would turn off the lights in front of the house and make Laura and me sing church hymns at the top of our lungs to drown out any doorbell sounds. We were the only kids who came to school the next day with no candy. Even so, other than each other, our grandmother was the most important person in the world to us. She taught Laura and me to respect ourselves and to become highly self-sufficient. Most important, she taught us how to be strong women.

We were everything to her. The two things that Grandma loved most were God and her granddaughters. When we were teenagers, the nice people at the nursing home would tell us that the only names our grandmother ever brought up were Laura’s and mine.

“Where’s Lisa and Laura?” she would ask each morning. “Are Lisa and Laura coming to see me today?”

We lost her in 1991.

Our mom moved to L.A. shortly after the divorce. She started working as an office manager in a law firm and moved up the corporate ladder quickly. We saw her fairly often. She would fly to Sacramento at least once a month and stay for three days to a week at her sister’s home. During the hours when Dad was at work, Mom would hang out with us in the house. We loved when she would bring us cool clothes from L.A., and all the kids envied our stylish new wardrobe. The clothes masked a lot of sadness. We would have given it all up in a second to have both of our parents together and happy.

Laura and I became seasoned travelers at very early ages because Dad would put us on a plane to spend the summers with our mom down south. A lot of the flight attendants came to know us; we were two little girls on a very big plane. Having each other made the hard parts so much easier.

Despite our challenging beginnings, Laura and I remained very close to both of our parents. They were both victims of circumstances that were larger than they were, and Laura and I have always been proud of the way they tackled so many of the issues that confronted them as young people. In the end, our parents’ divorce may have been the best thing to happen to us because they were so unhappy with each other. But when we were going through it, it was a nightmare. I think Laura was too young to remember most of the dark and ugly episodes that occurred when we were kids, but I wasn’t. Holes in the walls and broken objects litter many of my childhood memories. As the sounds of yelling and shrieking cries were coming from downstairs, I would look over at the baby girl and think—I just want to protect her.

Now we were all grown up, and she was in trouble.

LAURA

OVER THE NEXT DAYS and nights, I fell into what seemed like a black hole that included daily interrogations, psychological intimidation, and virtual isolation. Some nights after I’d been grilled all day about my past jobs and other assignments, I curled up into a ball in a dark corner of my room and sobbed profusely, wishing I could make myself small enough to just disappear. I feared I might never see my sister, my parents, and Iain ever again. I hated myself for putting my family through such pain.

For a few days, I was worried that I might actually be pregnant. Although I couldn’t bear the thought of giving birth and raising a child in a North Korean prison, a part of me hoped I had a baby inside me. It made me feel less alone thinking that I might be carrying a child. I also thought that being pregnant might cause the North Korean authorities to be more sympathetic to my situation. Maybe this child is a gift from God, I thought. Perhaps I was meant to get pregnant here so the baby could save Euna and me by giving the authorities the compassion to release us.

Days later, whatever fears or fantasies I had were put to rest. Any chance of being pregnant was gone. I was both relieved and demoralized. It crushed my heart to think I might never get to start a family with Iain. Though he was anxious to have a child, Iain had been patient with me while I pushed aside the idea of having a baby and instead focused on my career. Now, I thought, the chance might be gone forever.

I tried my best to keep my mind from wandering and longing for my family. I knew I needed to concentrate on the investigation so I could satisfy the authorities with my answers. I also wanted to be careful not to endanger any of our defector contacts or get myself in any more trouble than I already was.

During one interrogation session, Mr. Yee started asking me about my or my company’s ties to the U.S. government.

“Al Gore is your chairman,” he began. “So is your company connected to the government?”

“No, not at all,” I answered. “Vice President Gore wanted to start this company so that all people would have a voice in the media, not just the big corporations. It’s a network where anyone can participate. For example, if you disagree with what’s happening in North Korea, you can comment about it on our Web site. And if you agree and support the North Korean government, you can voice your opinion too.”

“Then who is funding your project here? Are you receiving money from the U.S. government to produce this documentary?” he asked.

I knew what he was asking and was afraid he might think that the company or I was being bankrolled by the CIA. I tried hard to convince him there was no connection whatsoever to the U.S. government. I went into a detailed explanation of the U.S. cable business, the media conglomerates, and advertising. He seemed genuinely intrigued and often interrupted me to ask questions about how advertisements work and about the various tiers of cable packages that consumers can choose from. Still, the question of whether or not the U.S. government was involved in our documentary would continue to rear its head multiple times throughout the investigation.

EVERY FEW DAYS a doctor and nurse visited me and cleaned my head wound. The doctor, a slim man with a nervous twitch, often gave off loud sighs as he inspected the area, causing me to worry. But each time, he assured me there was nothing to be alarmed about. The nurse transferred a cotton pad soaked in alcohol to his metal tong, and he rubbed that around the wound. Every time the alcohol touched the affected area, it would feel like a thousand needles sticking me. Rather than stitching the gash, the doctor preferred to let it close up on its own.

Since the beating, I had been having frequent headaches. When Mr. Yee asked me how I was feeling, I told him about the shooting pains in my upper left lobe.

“You’re young. You will get better over time,” he replied. “I wish you hadn’t resisted when the soldiers apprehended you. You know what happens when you resist arrest in the United States, don’t you? It goes on your police report.”

All I could do was nod in agreement, even though I was fuming inside. There was nothing to be gained from showing him my fury. Still, I didn’t want him to report that I had opposed the soldiers on the border. I stopped myself from blurting out, “In the United States, police brutality is a crime!” But I couldn’t just sit there and accept this lie. “I did not resist, sir,” I said defiantly. “Do you really think a girl of my size would challenge a fierce soldier with a rifle?”

Mr. Yee never accused me of resisting arrest again, and I refrained from complaining about my throbbing head.

Each day these rigorous interrogation sessions became a delicate balancing act. I tried to answer the questions while being careful to avoid revealing information that might endanger our sources or the interview subjects who had opened up their lives to us. Early on in the questioning, I told Mr. Yee that our team had received guidance from a pastor who worked in Seoul. Pastor Chun Ki-Won and his network, the Durihana Mission, have helped hundreds of North Korean defectors escape from northern China via a so-called underground railroad that takes defectors through treacherous terrain in countries including Laos and Thailand. Once inside these countries, defectors apply for amnesty through the South Korean diplomatic mission. If their request is granted, they are flown to Seoul to begin new lives.

The North Korean reg

ime sees Chun as an enemy. I knew I needed to confess our connection to him because he was such a central figure in our project. But I feigned having no recollection of his name or that of his missionary group. I could tell this was frustrating to Mr. Yee, who kept asking me how I could forget the name of someone with whom we’d worked so closely.

“How can you call yourself a journalist and not even know the name of someone you interviewed?” he asked.

“Korean names are very difficult for me to remember,” I said. “That’s why I just called him Pastor the whole time.”

Mr. Yee questioned me about Chun for two full days, and as time went on, he became increasingly annoyed that I would not divulge his identity.

“We already know his name,” he finally said on the second day. “His name is Chun Ki-Won.”

I tried to hide any sign of acknowledgment. Irritated, he asked, “Do you want to still deny that Chun is the person who helped you? Might I add that when you are speaking to me, you are not speaking to me as your investigator, you are speaking to the DPRK law!”

“I honestly don’t remember his name,” I said. “If that’s what you say his name is, then I’m sure you must know what you’re talking about. All I know is that I called him Pastor, and since I am speaking to DPRK law, I don’t want to lie.”

Somewhere Inside

Somewhere Inside