- Home

- Laura Ling

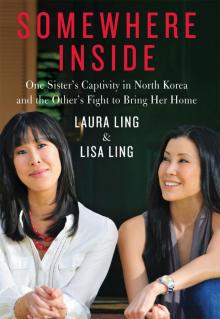

Somewhere Inside

Somewhere Inside Read online

Somewhere Inside

One Sister’s Captivity in North Korea and the Other’s Fight to Bring Her Home

Laura Ling and Lisa Ling

Dedicated in the hope that all people

will one day experience freedom

Map

Contents

Map

Author’s Note

Preface

One Somewhere Inside North Korea

Two Scrambling for Answers

Three Going to Pyongyang

Four The Visit

Five The Confession

Photographic Insert

Six The Phone Call

Seven The Window Is Closing

Eight Glimmers of Hope

Nine The Envoy

Ten The Rescue

Epilogue

Mom’s Special Watercress Soup Recipe

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

authors’ note

THIS IS A WORK of nonfiction that is primarily about our experiences in 2009 when Laura was seized by North Korean soldiers and held in that country for nearly five months. Laura has given names to some of the people she encountered in North Korea, but she never actually knew their real names and referred to them, if she did, as “sir” or “ma’am.” She has also changed the names of North Koreans whom she interviewed before her apprehension to protect their identities. Lisa has changed the names of two people she worked with, at their request, to protect their anonymity.

preface

WE WERE JUST FOUR and seven years old when our immigrant parents divorced. Few other parents at the time were separating in our all-American suburban community, and that filled us with insecurities and confusion. At least we had each other and could be each other’s protector and close confidante. It is impossible to measure the bond that formed between us.

Our grandmother lived with us during our parents’ divorce. She was a lady of strong Christian faith and character, and she encouraged us to be determined women and to stand up for people who didn’t have a voice. We took her words and lessons to heart.

As kids, we fantasized about escaping to distant lands. We played a game that involved a spaceship that could transport us from place to place, where we could embark on amazing adventures, battling villains and coming to the aid of those in need.

As adults, we found that through journalism, we could open people’s eyes to what was happening in the real world, just as Grandma had encouraged us to do. Between the two of us, we’ve spent more than twenty-five years traveling the globe.

We’ve seen things during our journeys that have moved us, from an Indian sex worker who has devoted her life to saving girls on the street, to ex-gang members in Los Angeles trying to bring positive change to their communities, to people rescuing children from child-trafficking rings in Ghana. We’ve also encountered things that have scarred us, from women violently gang-raped in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to people forced into slavery in the jungles of Brazil, to whole communities ravaged by toxic pollutants in China.

These experiences have filled us with a desire to tell the world about the people we’ve met and the things we have witnessed. We have been driven by a passion to try to be the eyes and ears for people who wish to explore unfamiliar cultures.

When, in March 2009, one of us got into trouble while reporting a story about the thousands of people being trafficked from North Korea into China, the other one jumped into action to try to help. Our bond as sisters and best friends got us through this horrifying time, even though we were thousands of miles apart. We drew strength from somewhere inside.

During this period of darkness, we experienced rays of light. They came in the form of unexpected relationships that evolved even in this time of crisis. One of us developed a better understanding of her captors and they of her. The other was helped by loads of people, many of whom she’d never met, who showed up to offer support.

Throughout it all, we were able to experience what happens when human beings get a chance to interact face-to-face, eye-to-eye, even if their countries are “enemies.”

This is our story.

CHAPTER ONE

somewhere inside north korea

Dearest Lisa,

Please do not share this letter with Mom or Dad, as I do not want them to worry. I am trying so hard to be strong, but it gets harder and harder every day. It is so difficult to get through each day. I miss you all so much it hurts. I want my big sister.

As I’m sure you know, I am in the worst possible situation….

LAURA

WE ARRIVED IN YANJI, China, on March 13, 2009. The mountainous region that borders Russia and North Korea is one of China’s coldest. As our team walked out of the airport, I clenched my fists tightly and hid my face in my woolen scarf to protect me against the bone-chilling, cloud-covered night. Over the past decade, I have made more than half a dozen trips to China—it’s where my father and his forefathers are from, and it’s always been one of the most fascinating places to work as a journalist. I’d reported from different parts of the vast country, but this was my first time in the northeast, where a large portion of the population is of Korean ancestry. The project we were working on had as much to do with something happening in neighboring North Korea as it did with this part of China, and being in Yanji, I could immediately sense a connection between the Korean and Chinese cultures. Signs are written in both Korean and Chinese characters; most of the restaurants serve Korean food. It would be easy for someone of Korean descent to blend in, without knowing a single word of Chinese.

Our small team consisted of producer/cameraman Mitchell Koss, coproducer/translator Euna Lee, and myself. We had traveled to the area to investigate a controversial issue to which neither the North Korean nor the Chinese government wants any attention drawn. Millions of citizens of North Korea, one of the most isolated, repressive countries in the world, suffer from dire poverty and brutal conditions, and some of them take the risk of fleeing, or defecting, from their homeland by crossing the border into neighboring China. But once in China, they end up facing a different kind of degradation.

China classifies these defectors not as refugees, but as illegal immigrants so rather than finding safe haven across the border, most of them end up in hiding, living underground in fear of being arrested by Chinese authorities. Those who are caught and repatriated back to North Korea could be sent to one of the country’s notorious gulags, where they face torture or possibly execution.

Most of these defectors are North Korean women who are preyed on by traffickers and pimps. These women escape from their country to find food; some are promised jobs in the restaurant or manufacturing industries. But they soon find out that a different, dark fate awaits them. Many end up being sold into marriages or forced into China’s booming sex industry. I wanted to open people’s eyes to the stories of these despairing women who are living in a horrible, bleak limbo with no protection or rights.

On our first night in Yanji, our three-person team arranged to meet up with the man we’d hired to be our guide. He was referred to us by a Seoul-based missionary, Pastor Chun Ki-Won, who has become a kind of legend in the area for helping North Korean defectors find passage to South Korea through an underground network. Our guide had worked with Chun as well as other foreign journalists in the past. He was also a kind of smuggler himself, with deep connections in North Korea. He claimed to have a clandestine operation in North Korea that loaned out Chinese cell phones to North Koreans and, for a fee, let them call relatives or friends in China or South Korea. Telephone use is strictly controlled in North Korea, and making calls outside of the country without permission

is almost impossible and dangerous.

We met our guide, a Korean-Chinese man who appeared to be in his late thirties, at our hotel to discuss our plans. His reserved demeanor and deadpan expression made him a hard read. We were hoping he could introduce us to some defectors and take us to the border area where North Koreans make their way to China. He said he could make the arrangements, but emphasized the risky nature of our investigation. We knew we would have to be cautious and discreet so we didn’t put any defectors at risk of deportation.

Before leaving for China, our team had decided to forgo applying for journalist visas. Normally, foreign journalists working in China are required to have a special visa and must also work with a Chinese media entity. But because of the nature of our story and the sensitivity with which the Chinese government regards the issue of North Korean defectors, we decided to enter the country as tourists. We didn’t want to draw attention to the people we were interviewing, so as not to endanger them or ourselves. We would be careful to conceal the identity of defectors when we filmed them, focusing on body parts or the backs of heads rather than faces or easily identifiable features.

LISA

I HADN’T BEEN PARTICULARLY worried about Laura’s assignment to the Chinese–North Korean border. A month earlier she had been in Juárez, Mexico, a city that had a higher death rate than Baghdad. The Los Angeles Times regularly carried headline stories about law enforcement officers and journalists being attacked by narco-traffickers. Every day Laura was there, I was struck by episodes of paralytic concern. She and her producer were shadowing Mexican homicide reporters who were chasing death. The documentary that aired showed one gruesome crime scene after another—from corpses left in a trash-filled ravine to mutilated bodies riddled with dozens of bullet holes. Needless to say, our family breathed a major sigh of relief when Laura was finally back from that assignment. She was so preoccupied with getting the Mexico show on the air that she never even told me she was going to Asia several weeks later. It was almost an afterthought when she mentioned that soon she would be leaving for another trip.

“What are you doing?” I pressed. “You just came back. I thought you were going to stop traveling so much.”

“I know, Li,” she replied. “Don’t worry. Everything is already set up.”

Laura and her team were headed first to Seoul and then to China’s border with North Korea to meet up with contacts and do some prearranged interviews. The trip was supposed to last a week and a half. My husband, Paul, even made a dinner reservation at a new barbecue restaurant for the Friday of Laura’s return. Still, none of us, including our parents and Laura’s husband, Iain, were eager for her to go. She had just wrapped up an extensive assignment, and we felt she had been working too hard recently. But arguing with Laura was pointless. She had always put a great deal of pressure on herself. She never stopped working.

Whenever we were together, she constantly checked her BlackBerry no matter what was going on around her. I’m a self-professed BlackBerry addict too, but Laura put me to shame. I found myself constantly frustrated by her lack of attention to anything but work. A few times I noticed it taking a toll on Iain. More than once I tried to scare her by telling her she better start paying more attention to her husband or he might find someone else who would.

LAURA

FOR THIS ASSIGNMENT ALONG the Chinese–North Korean border, one of my two colleagues was Mitch Koss, someone with whom I’d been working closely for the past several years. Mitch had been a mentor to me, a driving force in my decision to pursue journalism. I also considered him a member of my extended family. He’d worked with my sister, Lisa, when she was just starting her journalism career. After Lisa left Channel One News, where she and Mitch had worked together for five years, he approached me to help him with an assignment as a researcher. I jumped at the opportunity.

Over the years, Mitch and I worked on more than three dozen stories spanning the globe, including a visit in the summer of 2002 to North Korea’s capital, Pyongyang, where we, along with the Korean-American tour group to which we were assigned, were taken on a highly monitored tour of the capital’s most impressive monuments and sights.

Then in 2005 I was hired by Current TV, former Vice President Al Gore’s cable network, to develop its journalism department. Mitch was also brought on board by Current to advise other young journalists. Each week, our unit produced a half-hour investigative documentary program called Vanguard. In addition to my role as manager of the sixteen-person team, I was also one of the on-air correspondents, reporting from various locations around the world. In the past year, I had covered China’s restive Muslim population, life on parole in America, and Mexico’s drug war. Now I was here in China’s frigid northeast reporting on the trafficking of North Korean women.

My other colleague, Euna, was an editor in our journalism department. Because of her fluency in Korean, she was working on the project as a translator as well as a coproducer. Euna is a Korean American and I knew this made her particularly devoted to the assignment. She had been in communication with Pastor Chun in advance of our trip and, with his help, made most of our filming arrangements.

On a hazy, overcast morning, one day after our arrival in Yanji, our guide drove us two hours away to a logging town along the Chinese–North Korean border. We arrived at a small, dusty village where we met with Mrs. Ahn, a woman who appeared to be in her early fifties. She had fled North Korea in the late nineties at the height of a devastating famine. Estimates vary, but it’s believed that anywhere from hundreds of thousands to perhaps two million people died as a result of the famine. Conditions were so dire during that time that many North Koreans attempted to escape to China, where they heard they could get white rice, which had become virtually nonexistent in North Korea. Defectors, including Mrs. Ahn, bribed North Korean border guards to let them cross the river into China. Some hired so-called brokers to guide them across the treacherous waters. But once in China, many found themselves lost, with no way to make a living. The brokers, taking advantage of their vulnerable state, ended up selling these desperate women to Chinese men as wives.

The selling of women as brides is becoming increasingly rampant throughout China. In 1979 the Chinese government, in reaction to its exploding population, began limiting to one the number of children Chinese couples could have. The policy became known as the One Child Policy. What the government did not anticipate was that so many couples would want that one child to be male. As a result, tens of thousands of Chinese baby girls were aborted or abandoned, and today the country has tens of millions more males than females. Already men are having a difficult time finding wives, and women are being trafficked from other parts of the world, including North Korea, to fill this role. The women are sold off like animals to Chinese men, many of whom live in China’s impoverished countryside. While these women may receive more sustenance living as purchased brides, they exist without residency certification or identification cards, which means that at any point they can be arrested and sent back to North Korea, where they face certain punishment.

Not only is the reality grim for these women defectors, but the children they bear to Chinese husbands also suffer. The Chinese government does not view the marriages of North Korean defectors to Chinese men as legitimate and therefore does not recognize these children as citizens. If the mothers are repatriated to North Korea or resold to other men, as sometimes happens, the fathers often end up abandoning the children. Some of these children are cast away because their fathers are too old and disabled to care for them. With no identification cards, they are unable to attend school, and they are denied health care; they must live in the shadows as stateless children. At a clandestine foster home run by a missionary in Pastor Chun’s network, we met with a half-dozen foster children between the ages of six and ten who were being given clothes, a warm, clean place to live, and an education. It was hard to realize that without the help of Chun’s group, these young souls might be roaming the streets without any

parents or a government to provide for them. They would be lost and without identities.

Although conditions have improved in North Korea since the famine of the 1990s, a new generation of defectors is fleeing the country because the situation remains bleak and hunger is widespread. North Korea has maintained its overwhelming control over its citizens in part because of a propaganda machine that over the years has caused its people to believe that the rest of the world has been suffering even more than North Korea has. But little by little, information seems to be seeping into to the country.

The demilitarized zone, or DMZ, separating the two Koreas is the most heavily fortified border in the world. Soldiers on either side patrol their respective area along the thirty-eighth parallel, where in 1953 U.S. administrators divided the peninsula, three years after the start of the Korean War. The war was suspended by an armistice, but it never officially ended, meaning that the two sides are technically still at war. Because of the DMZ’s impenetrable barrier, where on one side thousands of U.S. troops support South Korean forces, and where nearly a million North Korean soldiers are stationed on the opposing side, it has been relatively easy for the North to keep information from high-tech South Korea from flowing into its country.

China, on the other hand, is North Korea’s closest ally. The border between the two countries is extremely porous. In many areas there are no fences or actual barriers, only a narrow river, separating the two countries. As a result, a thriving black market has emerged in North Korea as Korean-Chinese businesspeople take advantage of the North’s isolation. Not only do products from China get across the border, so does knowledge about China’s economic prosperity. North Korea, the so-called Hermit Kingdom, is finding it harder and harder to keep information about the rest of the world from coming across its border.

Somewhere Inside

Somewhere Inside