- Home

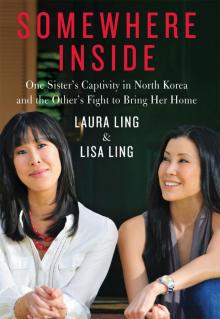

- Laura Ling

Somewhere Inside Page 4

Somewhere Inside Read online

Page 4

We’d been transported to a jail. Before entering the building, the soldier motioned for me to take off my shoes. He then unlocked a door that led into a small, dim area that housed a row of four cramped cells. The soldier removed a heavy lock from one of the cells, opened the door, and directed me into the dismal five-by-six-foot chamber. The deep echo of the door shutting and the lock clashing up against it made my skin crawl. Rather than having metal bars that allow one to see into each cell, these chambers were fashioned with heavy metal doors. There were two postcard-size slots in each door, one at the top for a guard to look through, and one at the bottom through which a small bowl of food could be placed. If the slots were closed, the room was pitch-black. Fortunately, a sliver of light entered my cell through an opening in the upper slot, and I could make out a thin pallet of wood on the concrete floor along with a pillow and two blankets. I sat down, buried my face in my hands, and began to sob.

I thought of Lisa, my parents, and my husband, Iain, and the horror they must be feeling not knowing where I was or if I was even alive. While in Seoul and China, I had managed to speak with Iain via webcam. But the time of our usual chat sessions had long passed. By now he must know that something was wrong.

CHAPTER TWO

scrambling for answers

LISA

PAUL’S PHONE JOLTED US AWAKE. I had turned my cell-phone ringer off before going to bed because I had been woken up by early calls from the East Coast the previous two days in a row. The clock read 2:30. It was the morning of March 17. Paul’s initial grogginess quickly turned to seriousness as he passed the phone to me. It was Laura’s husband, Iain.

“Laura’s been abducted by North Korean border guards,” he said.

I couldn’t respond. I just froze.

Iain explained that the producer/cameraman Mitchell Koss had evaded capture and was able to get a call out to his wife, who contacted one of Laura’s work colleagues, who then called him.

“Have you called my mom?” I asked.

“No,” Iain replied. “Should we tell your parents yet?”

“Yes, we need Mom to start reaching out to Chinese government offices,” I said, meaning that we needed my mother’s proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. “I’ll call the U.S. Embassy in Beijing right now.”

I also left an urgent message for my friend Richard Holbrooke, the U.S. special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan and the most senior diplomat I knew. Richard had been a foreign policy mentor of mine since my former boss at ABC TV’s The View, Barbara Walters, introduced me to him in 2001. Richard helped broker the peace agreement between warring factions in Bosnia in 1995. He was also U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in the Clinton administration and had worked extensively in Asia throughout his career as a diplomat. I knew he was very close to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, so I called him, hoping he could at least tell me what to do next.

By 4:00 A.M. I was on the road, headed to my mom’s house in the valley, which is about a twenty-minute drive from my home in Santa Monica. Iain, Paul, and I would practically live at her house for the next few months. As soon as Dad got the news, he flew down from his home in Sacramento to be with us. We based ourselves at Mom’s house because hers was the biggest and had the most bedrooms. We brought our essential items, set up our computers, and turned the place into our own Ground Zero in our efforts to get Laura home. We reached out to Euna’s husband, Michael Saldate, and their four-year-old daughter, Hana, and told them to make our home theirs. Euna’s parents were in South Korea and her sisters lived in other U.S. cities, so Michael and Hana became extensions of our family. They would spend many weekends with us at my mom’s house. Though we took the lead on release efforts, we wanted Michael and Hana to know that we would be working tirelessly on both Laura’s and Euna’s behalf.

We also phoned Joel Hyatt, the CEO of Laura’s employer, Current TV, and asked if he could wake up Current’s chairman, former Vice President Al Gore, right away. If this became the international incident we thought it would be, we needed Vice President Gore to flex his political muscle. As soon as he got the news, Gore got my phone number from Hyatt and called me; it was about 6:00 A.M. His deep southern voice was comforting. My sister had a very good relationship with the former vice president and I know she revered him, but except for a couple of brief exchanges at special events, I didn’t really know him. He put me at ease right away. With calming authority in his voice, he told me our family should trust that he would take control of the situation. This was a huge relief for us.

“I’ve been briefed by Joel about what’s going on,” he said. “As soon as people start getting into the office in Washington, I will start making calls right way. You call me anytime, and tell your parents that we are going to do everything we can to get Laura and Euna back as quickly as possible.”

Our conversation was not a long one, but I felt lucky to have the former U.S. vice president on our team. If anyone could open doors, surely it was Gore. He gave me all of his contact information and told me to share it with Iain and everyone else in the family. But there was something of vital importance that he suggested we not do: talk. He strongly advised us not to say a word to anyone, especially the press. At this point, no one knew what had happened to Laura and Euna. That wasn’t surprising, because so little is known about what goes on inside North Korea. He warned that we did not want to do or say anything that might inflame those holding my sister and Euna. We had to exercise extreme caution.

“The next forty-eight hours are crucial,” he urged. “We’re not dealing with a normal government, and we have to be very, very careful.”

LAURA AND I HAD faced unpredictable situations before throughout our careers. We both started working as journalists when we were very young, and we’d traveled to dozens of countries, some of which were unstable during our visits. When I was eighteen years old, I was hired to be a correspondent for a news program that was seen in middle and high schools across the country; it was called Channel One News. Channel One routinely sent correspondents all over the world to cover stories that network news wasn’t covering: we reported on the civil war in Algeria, globalization in India, sex slavery in Saipan. For a kid who’d never gotten a chance to travel, Channel One opened the world to me. It exposed me to distant lands and foreign cultures and broadened my sense of humanity in ways I would have never been able to experience otherwise.

Early on in my tenure at Channel One, I started working with the man who became my mentor and eventually my sister’s, Mitchell Koss. This was the early nineties, and our style was drastically different from what traditional news was doing. First off, Mitch became the cameraman as well as serving as producer. So unlike most news crews, which required a sizable number of people, we were compact and easily mobile, and because it was just the two of us, we were cheap. Our style was casual and experiential, and we immersed ourselves in the stories we covered, giving viewers a very accessible kind of reporting. We went to the front lines of the war in Afghanistan, to the cocaine-producing jungles of Bolivia, and to Tibet, where twice we went in posing as tourists.

We were able to do this because we didn’t have to shoulder the weight of a big, well-recognized news organization. Journalists on official visits to China must provide a detailed list of intended shoot locations and interview requests, and they have to provide a letter of invitation from a Chinese organization. If granted, an escort from the government is assigned to monitor every step and word inside the country. We knew that if we acquired official journalist visas from the Chinese government, we would not be able to cover the kind of story we wanted to cover in Tibet. As tourists, we could capture a much more realistic, nonpropagandistic look at the reality of life there. When we stopped in a Buddhist temple, two young monks approached us and whispered that a year ago Chinese police officers had taken a few monks away from the monastery, and they’d never come back. I was struck and humbled by how brave these monks were to talk to us. They were literally risking their liv

es to alert us to what Chinese officials had done to their brethren. We would never have had such candid conversations had we gone in as journalists. Going in officially would have inevitably skewed the story in one direction, China’s.

During my seven years as a reporter at Channel One, Mitch and I crisscrossed the world several times over. I relished every second of my job at Channel One until it was time to get a TV job that people outside high school would see.

That’s when, in August 1999, I was offered a job as cohost on the daytime talk show The View. Later that year, Laura became a researcher at Channel One. After working with me for so many years, Mitch had become a close family friend. So it wasn’t surprising that when she started at Channel One, Laura began to work with Mitch as well.

LAURA

I WAS A COLLEGE STUDENT at UCLA when Lisa’s career began to take off. I looked at her work with both pride and envy. She made me want to know more about what was happening in the world; she made me care about things I would never have known about. Her reports opened my eyes to what was happening in Cambodia, Iraq, and Kazakhstan, places that few people were paying attention to. I was left not only wanting to know more, but yearning to travel the world myself and investigate new situations.

Working at Current TV, a new cable network that targeted the young adult demographic, gave me, along with a team of journalists, the opportunity to raise awareness about critical but underreported issues. Our department was called Vanguard because, at a time when most news networks were cutting back on the number and kinds of stories they were covering internationally, we sought to fill the void.

Like my sister, I had become accustomed to reporting in hot spots. Just a few months earlier I had taken on one of the more dangerous assignments of my career. Along with Mitch Koss and an associate producer, I’d traveled to different cities in Mexico to report on the escalating drug violence that was paralyzing the country. Warring cartels were battling with each other and the Mexican government. In Ciudad Juárez, which borders El Paso, Texas, we rode with a local journalist to places where half a dozen gruesome homicides had taken place. A cemetery in the city of Culiacán revealed an endless patchwork of graves representing a generation of young men murdered in the narco-war.

Lisa and I worried about each other during every risky assignment and made sure to check in regularly. Lisa was relieved when I finally finished the Mexico project. Before I left for Asia, she told me to hurry up and get home so I could slow down and start trying to have a family. She knew I had been thinking about having a baby for a while, but the pace of my job kept interfering.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “There won’t be any bullets flying on this story.”

Now I was sitting in a North Korean jail—I hadn’t expected this project to be physically dangerous at all. My biggest worry had been about protecting our interview subjects. But I never could have predicted this situation. I thought back to the conversation I had with Lisa about slowing down. The morning of my flight, I told her that Iain and I were finally trying to start a family.

“Who knows?” I said, smiling. “I could be pregnant right now.” Those words rang through my head. What if I were pregnant?

My thoughts were interrupted by the clanging of a small tin that was being pushed through the lower slot in the door. It was a metal bowl of rice with a few pieces of kimchi, a traditional Korean dish made of cabbage and spices. My jaw was still aching from the soldier’s kick with his boot; it was a challenge to open my mouth. I forced myself to take a few bites to keep up my strength. Soon after dinner, I heard a guard open the cell door that was to the left of mine. I could make out Euna’s soft voice inside. A feeling of relief rushed over me when I discovered that at least she was nearby.

I had known Euna for more than four years. She’d edited a number of projects for Current TV’s journalism department, many of which I had worked on personally. Together we’d sit in one of Current’s cramped editing rooms and scan through the videotape from a particular shoot, trying to find just the right image that would make a scene come to life. Euna always had a photo of her adorable daughter, Hana, pinned up somewhere near her computer screen. Although this project along the Chinese–North Korean border was the most extensive one we’d engaged in together, being out in the field with Euna felt natural. While I didn’t know her well personally before this trip, the events of the last twenty-four hours had bonded us for eternity.

I peered through the slot in my door and saw Euna exit the room followed by a uniformed soldier. Several minutes later, I too was taken out of my cell into a separate interrogation room. I was met by two male officials and a female translator. The first man was tall, robust, and handsome. The other was of average height and heavyset. Unlike the other authorities we’d dealt with earlier in the day, these men were not wearing military uniforms. Both were dressed in the typical North Korean attire—dark Mao-inspired suits with pins of the Korean flag—and they seemed even more intimidating. The translator had perfectly styled hair. She spoke in very broken English—between recurring coughing fits—and said she was an English teacher at the local school. I struggled to make out her words and wondered how well she understood me.

I took a seat, cross-legged, on the floor in the center of the room. The area consisted of two chairs, a glass coffee table, and a Chinese-brand television. But rather than sitting in the chairs, the officers plunked themselves down on the floor, leaning their backs against the wall. They began asking me questions through the translator about what I was doing at the river. I stuck to the story Euna and I had rehearsed and explained that I was a university graduate student working on a documentary about trade along the border.

“What other things were you filming besides being on the river?” they asked.

I told them about some of the merchants we had spoken with on the Chinese side of the border who were selling cigarettes, money, stamps, and herbs from North Korea.

After they asked some basic questions such as “How many students are in your class?” and “How many women students are there?” I knew this fabrication could not go on for much longer.

Fearing I might cause trouble for Euna if I came clean and told them what our true professions were, I decided to continue on with the lie until I had a chance to compare stories with her. I based my answers on the number of people who worked in our journalism department at Current TV.

“We have sixteen students,” I replied. “Nine of them are women.”

I hoped Euna was using the same logic. I later learned that she said we were the only students in our class; that it was a kind of independent study program.

“You’re lying!” shouted the translator on behalf of the taller officer. “Do you know that as an American, you are an enemy of my country? Why would you want to come to my country if you were not invited? Euna Lee has been frank with us. If you are not frank with us…”

He then moved his hand across his neck in a slicing motion. I started to tremble and broke down in tears.

“You are being cunning!” the woman translated in a harsh, stern tone. “Don’t try to gain sympathy with your weeping. Do you think we are fools?”

I looked up into the official’s dark, narrow eyes. I felt the stabbing of his sharp gaze and bitter scowl. He handed me a pen and a few sheets of paper and told me to write down information about my family. They wanted the names, ages, and work history of all immediate family members and spouses.

I tried to think of a way to describe Lisa’s profession. I knew they could easily find out that Lisa was a journalist and that a simple Internet search could reveal her work on a controversial documentary she surreptitiously filmed in North Korea for National Geographic Television. That information could be hugely detrimental to my situation. But I wasn’t convinced that in this remote part of the country they even had the technological capability to access the Internet. “Sister—Lisa Ling Song,” I jotted down, adding Lisa’s husband’s surname to her designation. “Profession—housewi

fe and volunteer.” I figured I wasn’t lying completely. Lisa was a wife and a volunteer.

This questioning session went on for several hours. During this time, I often explained that I couldn’t understand what the translator was asking or saying. I tried to play ignorant so that Euna’s stories and mine would not conflict. At one point the electricity went out and the room went dark. A single flashlight provided light for the remainder of the evening. I would see that these blackouts happen multiple times in a day.

At one point I looked down at my jacket and saw fresh droplets of blood. I had forgotten about my injury. The events of that morning seemed like a lifetime ago. The wound had opened up again and my head began to throb. I remembered I had a few tablets of Tylenol in the bag I had been carrying when we were apprehended. I asked the officers if I could take them to alleviate the pain. They summoned a soldier to retrieve my bag and watched carefully as I rummaged through the contents until I found the package of pills. The interrogation lasted about six hours. A clock on the wall read 3:00 A.M. when I was finally escorted out of the room.

Back in my cell, I curled up on the wooden platform and pulled my bloodied parka over me as an extra layer of warmth. As I clutched the puffy winter coat, it was a reminder of my sister, who on the morning of my trip had driven all the way across town to see me off. She was concerned about the biting cold of northern China in March, so she rushed over to loan me her warmest clothes.

Suddenly a beam of light shone into the cell as the soldier standing watch aimed his flashlight through the slot in the door. His cold gaze sent daggers through my body. He slid the metal opening shut, and the darkness engulfed me. I was terrified to the point of breathlessness.

Somewhere Inside

Somewhere Inside